Research

One of the unique characteristics of human intelligence is the ability to learn and perform a diverse range of high-level motor skills. Unlike what many think, motor skills are richly cognitive. A soccer player can quickly read the field as to the movements of the ball, the wind, the position of opponents and swiftly decide whether, what, how, and when to act, all within a split second. Cognition is also crucial in allowing us to choose and generate the right actions, in the right order, and at the right time, when performing daily activities such as navigating a busy street while driving or crafting a cup of cappuccino for a friend.

In THINCmo Lab, we aim to uncover the cognitive and computational principles of motor behavior and skill learning. To do so, we integrate a combination of methods including psychophysics experiments, computational models, and patient studies. We hope to broaden our understanding of the complex human mind and movement, and to develop insights for applications in sports and musical training, rehabilitation, education, and human augmentation.

Motor learning across the lifespan

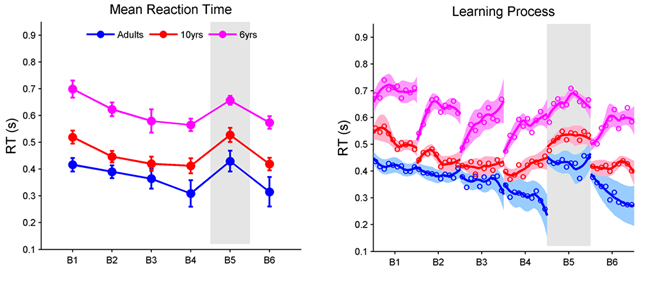

Healthy adults are often studied to uncover principles of motor skill learning, and these principles are then applied to help people learn or re-learn skills. Yet, childhood appears to be the best time to learn skills, as seen in children’s rapid acquisition of language and motor skill like riding a bike in daily life. But is this true? Do children learn differently than adults? If so, how? Can insights about learning in children benefit applications like sports training or rehabilitation?

In the lab, we actively explore these questions: Do children and adults learn motor skills differently? Are distinct cognitive processes engaged? What are the long-term benefits of distinct learning processes in terms of retention and generalization? And can we enhance learning by deliberately manipulating specific cognitive mechanisms?

Champions don’t do extraordinary things. They do ordinary things, but they do them without thinking, too fast for the other team to react. They follow the habits they’ve learned

— attributed to Tony Dungy or Charles Duhigg

Habit formation

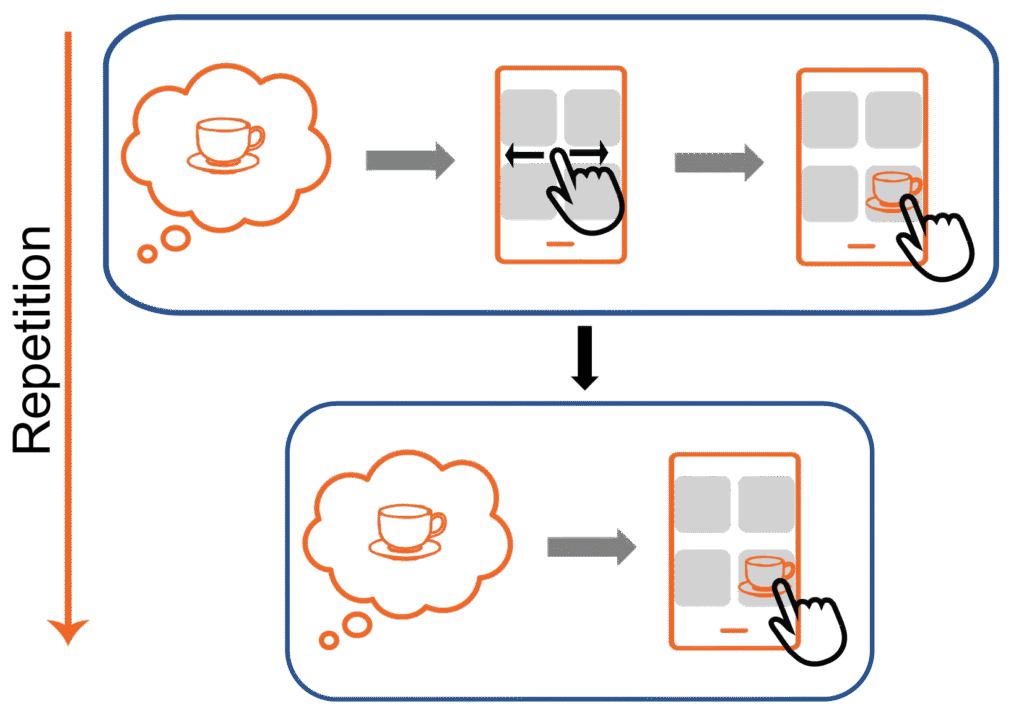

Behaviors repeated frequently often become habitual. In skill learning, forming habits through practice is generally thought to be beneficial as it improves response speed and reduce cognitive load.

However, the conventional view of habit as a direct stimulus-response association is too limited to explain complex human behaviors,. For example, unlike habits, skilled performance is flexible and can be adapted to changing situations. To resolve this paradox, we recently proposed that rather than a skilled behavior as a whole becoming habitual, habit formation occurs at the level of intermediate computations of a behavior.

In our work, we use a powerful experimental paradigm and computational models we built to examine when and how computation components within a single task becomes habitual. We are also interested in understanding the mental representation and computational nature of habit, and its precise relationship to automaticity, a hallmark of being skillful.

Habit extinction

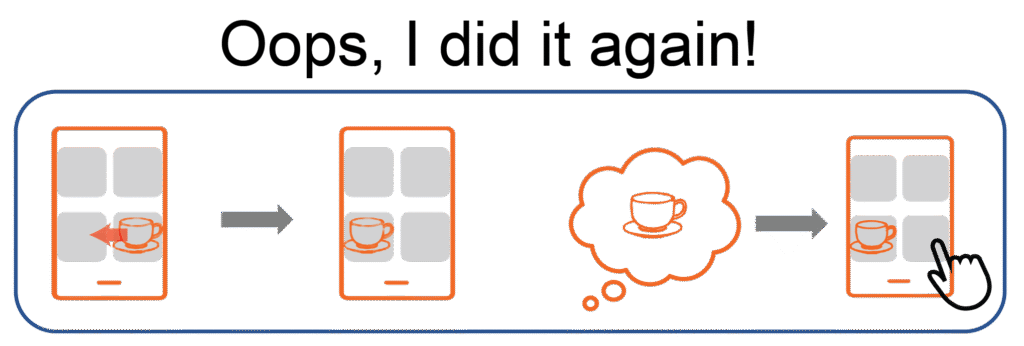

While good habits have a positive impact in performance and well-being, bad habits lead us to engage in persistent, unwanted behaviors. Being able to eliminate such unwanted habits is crucial to optimize skill learning and improve quality of life.

Although various practical interventions have been developed, their success is limited and old habits are vulnerable to relapse in the long term. The reason why breaking habits is so difficult remains poorly understood.

Using fine-grained experimental tools, we investigate whether old habit memory passively decays with time, are suppressed by newly formed competing memories, or can be eliminated altogether. We hope to leverage these insights to inform more effective, lasting strategies for habit extinction in real-world applications.

The diminutive chains of habit are seldom heavy enough to be felt, till they are too strong to be broken

— attributed to Samuel Johnson

Quitting smoking is easy, I’ve done it hundreds of times

— attributed to Mark Twain

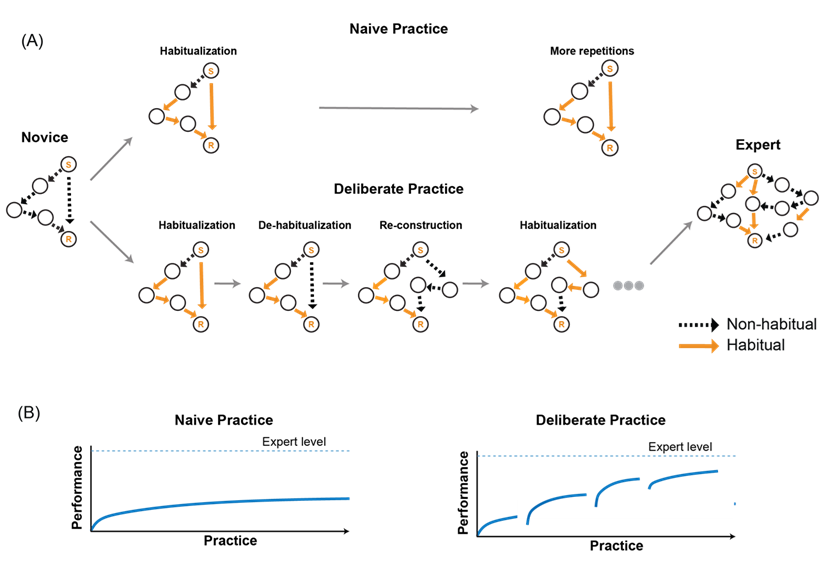

Deliberate practice toward expertise

In most lab-based experimental studies, people can reach high performance by merely repeating a task for just a few minutes or hours. However, this level of rapid improvement rarely occurs when learning complex real-life skills. Unlike simple lab tasks, real life motor skills pose the challenge of controlling and coordinating whole-body movements (e.g., many redundant degrees of freedom), navigating a much broader range of contexts and actions, engaging in much richer interactions with the environment, and demanding greater cognitive involvement. Yet, experts often posses a precise mental representation of the very difficult task they master.

At THINCmo, we study how people acquire new complex skills through deliberate practice (beyond mere repetition) and how mental representation of a complex task evolve through long-term deliberate practice.

Other research in our lab covers action control, sensorimotor synchronization, and mechanical reasoning